Philomena Lynott overcame extraordinary odds to raise her beloved

'only boy'.

Now she tells of the second son and daughter she gave up for

adoption

- and why she kept them secret for 50 years

- and why she kept them secret for 50 years

By JASON O'TOOLE, DailyMail.co.uk

Last updated at 8:46 AM

on 25th July 2010

The whole world knows how

hard Philomena Lynott fought to keep and raise her

son Philip – and what a job she made of it.

After all, her struggle

against poverty and racial bigotry in 1950s Ireland was the centrepiece

of her bestselling memoir – and her son, who she always calls Philip, went on

to become one of the biggest rock stars in the world.

That book, My Boy, made

much of her courageous resistance to attempts by over-zealous nuns to browbeat

her into giving up her only child for adoption.

That’s why her confession

today is as courageous as it is shocking. For the first time, she admits not

only to giving birth to two other children – a boy and a girl – but to surrendering

both of them for adoption.

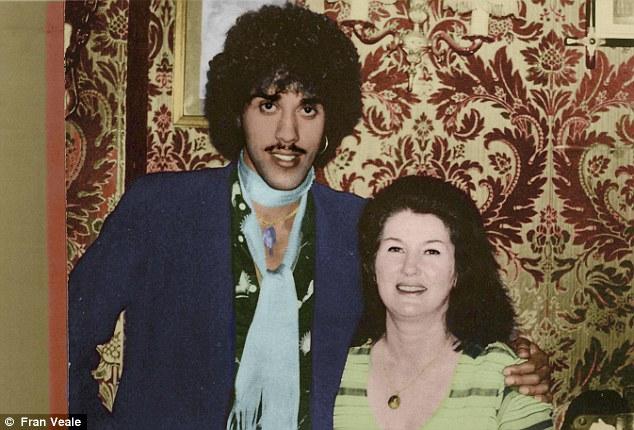

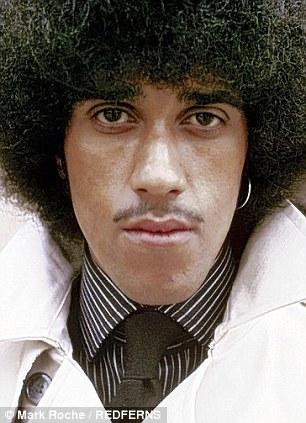

Bond: Rockstar

Phil Lynott was proud of his mother's fight to keep

him

With the 25th anniversary

of her rock star son’s tragic death just months away, it cannot have been easy

for Philomena to tarnish the myth she herself gilded in her book.

But, she says, she can no longer keep her secret bottled up. She ‘held

back a lot’ in her book, she says, because she had successfully concealed her

other babies from her own mother – and her ‘stomach was churning’ about her

ever finding out.

‘The shame was

unmerciful. I couldn’t let my mother know I had two more children. When I had

those children, to have children out of wedlock was a terrible thing. In my

day, to have a child out of wedlock you were a slut. You were classed as soiled

goods.

'It was awful,’ she says

as she finally opens up and tells her remarkable story in this exclusive in-depth

interview.

‘My sisters all knew –

but not mammy. At the time of doing the book, I was still heavily grieving. My

mother went to her grave not knowing I had two more children. I loved my mother

and she thought I was lovely. I took care of my mammy until the last. And that

was that. After she died, I didn’t care who knew.

‘Then my children got in

touch with me and we decided to perpetuate the secret because they also didn’t

want their adopted parents to know that they had gone and found their mother.

They visit me. They’re my best friends. I respect them. I love them. They love

me.’

The decision to give up

the two children she christened Jeannette and James was ‘horrendous’, Philomena

says – but she did it so they would have better prospects than she could give

them, struggling to make ends meet in the ‘slums’.

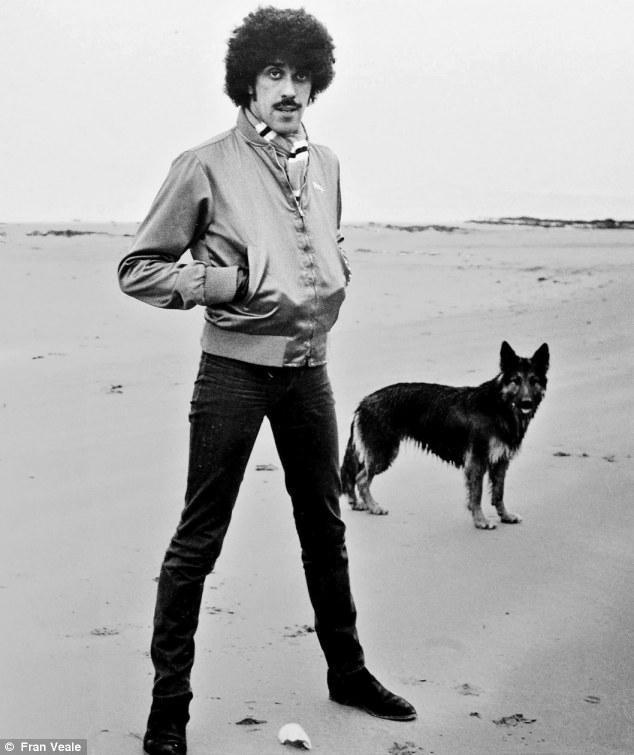

Buddies: Phil on the

beach at his home in Sutton with his pet Alsatian

‘Today, young women can

have babies and they can go to their mammy and say, “Mammy, I’m pregnant”, and

their mothers help them. The State helps them – they’re given homes and this,

that and the other,’ she says.

‘And thank God, the world

has changed for the young women who fall by the wayside. Now, to have a baby

within wedlock is unusual!

‘I got loads of letters

when I wrote my book from women who had had to part with children. The women of

today don’t know how lucky they are. They are not pressurised;

their mothers are not throwing them into convents, workhouses or anything like

that.

'They can walk around

with their babies, no wedding rings on and nobody cares. And that is lovely.’

Ostensibly, this

interview was arranged because Philomena wanted to voice her aversion to her

son’s old band Thin Lizzy’s plans to ‘cash in’ by

performing in Dublin on the night of his 25th anniversary next January 4th.

The contentious concert

will clash with the annual Vibe For Philo concert,

which has commemorated her son’s musical legacy on every anniversary over the

past the 24 years.

‘It’s terribly unfair to

the Vibe For Philo,’ she says. But

as we settled down to chat in her sitting room – where she has temporarily put

her own bed so she can be close to her dying dog – she unexpectedly opens up

about her secret family.

One of us: Phil, standing

second right, with neighbouring kids in Crumin

‘You don’t know what I

went through,’ she begins – and then the floodgates open, for eight hours, over

a two-day period.

Born in the Liberties on

October 22, 1930, Philomena is still in robust health and – despite battling

skin cancer last year and also suffering a massive heart attack when she was 70

– she looks remarkably younger than her 80 years.

She was four years old

when her family moved to 85 Leighlin Road in Crumlin, where her ‘only son’ would also be raised and

would first learn to play the guitar within the walls of the small terraced

Corporation house as he began his path to international fame and fortune.

She recalls: ‘I had a

lovely childhood. When I was 17, my two elder sisters and elder brother joined

the RAF in

‘So off I went to go

nursing in

‘My mother gave birth to

a son named Peter. Peter, my brother, is just

two years older than my son Philip.

They grew up together.

And Peter played guitar, too, and he was fantastic.’

Shortly after the birth,

the family ‘let me go back to England’ and destiny soon intervened when she met

Cecil Parris, from Georgetown, in British Guiana on the northern coast of South

America – not Brazil, as has been widely documented in the countless articles

since Philip’s tragic drug-related death.

'Yes, I held it all back

in my book. The shame was unmerciful...I couldn't tell Mammy'

In 1947, Cecil decided to

emigrate to

He met Philomena in 1948

in a dancehall attached to a Displaced Persons Hostel in

‘I never fell in love

with him. It was a “happening”. You’ve got to remember that I was 17 or 18 and

I didn’t smoke or drink but we used to go to these dances.

‘Philip’s father came all

across the dance floor and he asked for a dance and I couldn’t refuse him. I’ll

tell you why: it wasn’t in my heart. He had walked the whole length of the

floor and everybody looked at him. Remember, they didn’t want black to be

mixing with white.

‘It was fate – something

said to me to get up and dance. And when I danced, the floor got full of people.

He was a good dancer. When the dance was over, I walked back to where all the

women stood and they all backed off – I was a “nigger lover”.

‘Then, when I left that

dancehall that night, as I walked outside, two Polish guys that me and another

girl had been to a dance with started to grab me and he (Cecil) grabbed them

and protected me. And that’s when he said, “Would you like to go out with me?”

And I must have said yes.

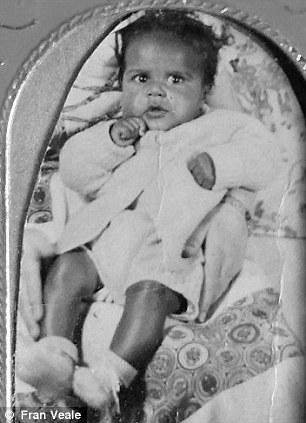

Fragile: Philip as a

baby. Having a black illegitimate child was 'the lowest'

‘That was the beginning.

And I had a few dates and the rest is history.

‘But there was no falling

in love with him at the time. I’m being very honest. There was no falling in

love but I must have felt a bit of compassion, that he’d been kind to me. He

was a good man.’

Philomena lost her

virginity to Cecil when they made love on a ‘local golf course’. Shortly

afterwards, Philomena was ‘horrified’ to discover she was pregnant, but by this

stage Cecil had already departed to work in

In fairness, Cecil had

written letters to Philomena at the hostel where she had been staying – not

knowing that she had been ‘ruthlessly expelled’ after they discovered she was

pregnant.

After a ‘naïve, failed

attempt’ to abort the pregnancy by drinking boiled gin ‘with some pennies in

it’ and then taking quinine tablets, Philomena began to accept her situation

and went to work in the foundry at the Austin Motor Company right through her

pregnancy.

‘I used to wear an

old-fashioned corset to keep my stomach in because I couldn’t let people know –

because I wasn’t married. And to have a baby out of wedlock in those days you

were classed as a tramp. You were classed as the baddest

of the bad.

‘I was taken from the

foundry in an ambulance to the hospital and I was 36 hours in labour. And all

the women were screaming, “Oh, George or Henry – never again!” I just lay there

and I suffered in silence.

‘Because nobody knew. None of my family knew

that I was having a baby. I couldn’t tell them, the shame was unmerciful.’

Weighing nine-and-a-half

pounds, Philip Parris Lynott was born on August 20,

1949. Soon afterwards, Philomena was forced to move with Philip into the Selly Oak Home for unmarried mothers.

However, Philomena was

bluntly told that she could only leave the home if she gave her child up for

adoption. She was told that a married couple were

‘willing’ to adopt Philip and that the nuns were making arrangements for her to

return to

‘But I wasn’t going to

let them take my child away from me.’

But Philomena was

terrified that her parents would discover she had Philip and the nuns played on

this fear, warning her that if she didn’t surrender the baby, her

‘conventionally respectable’ Catholic Irish family would be informed that she

had given birth to an ‘illegitimate black child’.

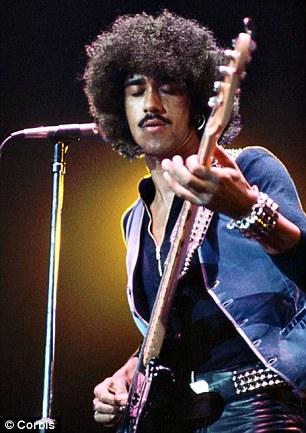

Phil Lynott

of Thin Lizzy on Stage

‘It was awful what they

did to me in that place. They put me out to work in the shed because I was the

lowest of the lowest – because I had a black baby. Even today, I live with a

bad back because it was freezing working in the shed – it was a stone floor.’

Eventually she was

rescued from this horrific experience when Cecil finally discovered he had a

son and miraculously tracked Philomena down. ‘He said, “I’ll find you somewhere

to live”.’

It was easier said than

done because racial prejudice meant that nobody wanted to take in a single

white mother with a black baby.

But eventually, after

many ‘point-blank refusals’, Cecil found a Mrs

Cavendish in the working-class suburb of Blackheath

who was willing to take them in – but there was one condition: Philomena would

have to share a bed with the landlady’s teenage daughter, Dorothy, while Philip

would sleep in the cot nearby.

‘And she p****ed all over me in the bed. She had

a slight mental problem,’ Philomena sighs at the recollection. But at

least Mrs Cavendish agreed

to babysit Philip while Philomena went off to work.

Unfortunately, she would

return home in the evenings only to discover that his nappy hadn’t been changed

once during the day.

‘I’d only have a few

hours with him, to cuddle him and nurse him and change him and clean his bum. I

said to Philip’s father, “Get me out of here”.’

She adds: ‘I met this

woman who was pregnant and she couldn’t tell her mother. The two of us ran away

and we ended up in

An African man gave us a

room but didn’t he try to come in and sleep with the two of us? So, we had to

run to the police. You don’t know what I went through.’

Cecil ‘found’ Philomena

in

‘But I wasn’t interested

because by then he’d become a bit of a flirt with the ladies,’ is all she would

say on the subject of their break-up.

But during this period in

Emotional: Philomena

broke down when she mentioned her son James

‘He thought it was his,

but he wasn’t the father. None of them has the same father,’ she reveals with

brutal candour. In fact, Philomena never told the

real father about the unwanted pregnancy.

And when Cecil ‘went back

to

‘I never saw him again

for a couple of years. I always told Philip that his father was a good man who

wanted to marry me, which he did in the early days. And I didn’t want to marry

him.’

Understandably, Philomena

says she couldn’t continue struggling to raise her children on her own because

she was close to ‘total physical exhaustion’ from the ‘obvious problems of

‘racism, loneliness and poverty’.

In her memoir, she tells

how she collapsed on the street when a bus conductor cruelly rang the bell –

signaling the driver to pull off – as she was attempting to clamber on with her

buggy. It was the last straw.

She decided to ask her

parents to take in Philip. But what she didn’t reveal until today is that she

also made the heartrending decision to give her daughter up for adoption.

‘That was heavy. Because

when I had the little girl, I was in digs, in slums, which was horrible. There

was a welfare nun who used to visit and she said to me, “You’re going home to

‘When I came back, she

brought Jeannette back to me and she was dressed up and she was full of toys.

‘She said, “Guess where I

took her? I took her to a schoolteacher and his wife”. They were trying to

adopt a little girl.

The nun said, “Philomena,

why don’t you let your little girl have a break? Because

you’re going to have to spend the rest of your life living in the slums.

This child will have a wonderful life”. That was how I let Jeannette go.

Consequently, she’s a

schoolteacher. She is a lady. She works with the church. She makes her own

honey. She makes her own wine. She is a beautiful person. She sends me the

lovely things that she makes and everything. We talk on the phone.’

Within 15 months of

giving birth to Jeanette, Philomena had a third child from a relationship with

a black GI called Jimmy Angel, an alias she gave when writing about their

affair in her memoir – which omitted, however, any mention of falling pregnant

with her second son, James, who was born in Manchester in June 1952.

‘When he went back to

‘The difference over

here, in this side of the world, was that no white man wanted his daughter

marrying a black man. Today, nobody cares; there’s so

many mixed children now, it doesn’t matter.

Phil Lynott:

Today there's so many mixed children. It doesn't matter.

‘It seems to me that

before he joined the army, he was courting another girl, so the grandmother

rang me and told me to “get knotted” and “don’t bother writing any more”.

He must have ended up

marrying this girl and he became a doctor. When you have an affair, you don’t

keep in touch. You have happy memories. But your life goes on.

So why did she give up

James? She says: ‘The boy got tuberculosis and they took him to a sanatorium in

Did Philip know he had a

half-brother and half-sister?

‘He didn’t know he had a

brother. I told him he had a sister because she had got in touch with me. And

the boy hadn’t at the time.’

After she wrote her

memoir, Philomena’s third child, James, finally made contact with her when he

approached the book’s publisher’s to ask them for her contact details.

‘When he found out who he

was, he got in touch with me. I arranged to meet him in the hotel up the road.

I sat there and he came through the door and I looked at him and he looked at

me and we broke down (crying).

‘He’d read that Philip

used to buy me 48 roses. When I got in his car, he had a bucket in the back

with roses and he had a book about Gregory Peck because he knew I loved Gregory

Peck.’

In 2003, it emerged that

Philip had a lovechild, Dara Lambe,

who had been given up for adoption by his mother. It’s another subject that

Philomena has not spoken publicly about.

‘I can answer you

straightforward: yes, he is Philip’s son. Oh, yeah, without a

doubt.’ He has the same thumbs – like Philip used to slam the bass

guitar – and eyes, she says.

As she finishes telling

me about her secret family, Philomena looks like someone who has been relieved

of a 16-tonne weight. Then she adds firmly that this will be the only time she

speaks in a newspaper about the two children she gave up for adoption.

‘I’ve said it now. I have

no more to say.’

Why didn’t I marry Denis? I would never say ‘I

obey’!

Even though Philomena

managed to find work and save up her money to eventually fulfil

her dream of running a successful hotel in

‘When I’d meet boyfriends

and maybe I’d have a second date I’d say to myself, “I like him. I might tell

him I have a baby and I’m not married”. I’d say to them, “I think I’d better

tell you, since you’ve asked me out a second time, I have a baby; I’m not

married”. They’d say, “Oh, it doesn’t matter”. “Well, but I’d better tell you

that my baby is black”.

‘After that, it was

trying to get me to bed because I was “a tramp”. And that went on for a long

time. Every time I met a man.

‘So, all I did was keep

working and working. I didn’t bother with men. Then one night, I went to a do

at a nightclub and Denis was there.’

Phil was 14 years old when

Philomena met Denis Keeley, the man she shared her

life with for 50 years before his death in January this year. She says Phil and

Denis ‘were great buddies’.

In an eerie coincidence,

Denis was cremated on January 4 – the same date Phil died. Sadly, it meant that

as Philomena was deep in mourning she was unable to attend the Vibe For Philo event for the first time in over 20 years.

‘It was heavy going. It

was horrendous. He died on the Thursday night and the Vibe was on the Monday.

And I love going to the Vibe because I love the music, I love seeing everybody,

and I stand up there singing – I’m an old rocker. I was heartbroken.’

She says the past 12

months have been mentally and physically exhausting for both herself and Graham

Cohen – a friend she describes as being like family – who helped her nurse

Denis through his battle with cancer.

‘I knew I was losing

Denis from last summer. He had deteriorated. We nursed him here; we wouldn’t

let him go to the hospital.’

‘He was 78 but he got the

lung cancer. He reckoned it was the cigarettes. He used to preach to me,

“Phyllis, stop that smoking, you’ll end up like me”.

‘It was awful. We had him

here for the last year of his life, taking care of him, me and Graham, waiting

on him. I was with him for 50 years. And we never married.’

Do you regret not getting

married?

‘Not at all. What for? To say, “I

do”?! No, I would never say “I obey”.

Giving them up broke my heart but I had to do it

Giving up her third

child, James, for adoption and, at practically the same time, sending

four-year-old Phil back to Crumlin to live with her

parents were the hardest decisions of Philomena’s life.

Her mother, after all,

was so mortified that she told the neighbours – and

even her own husband – that Philip, her grandson, ‘belonged to a black lady’

who tragically died.

But she says, not only

did her heart-breaking choice give both boys a better life, it also freed

Philomena to get her own life together.

‘I lived in slums and

Philip was going home to Crumlin, which was beautiful

in its day,’ she says. ‘Going home to Mammy and my brothers to be raised like I

was in that little house – warm, getting a dinner, pots of stew down him and

everything, and going to school, it was…’

Her voice trails off.

Like heaven?

‘Yeah,’ she says, adding:

‘And that allowed me to go and take the three jobs and send money to Mammy for

keeping him and then I’d send him his pocket money. I kept him very trendy; he

was the first kid in

‘And from that, I came

out of the gutter. I got myself three jobs – I was working a full week, I was a

barmaid at night, and I was doing markets at the weekend.

‘And I saved enough money

to put a deposit on the hotel. And I moved up in the world, instead of God

knows what would have happened to the three of them. They probably would have

been brought up in a slum area; God knows what they’d be. There they are and

they love me.’

In 1976, Phil disclosed

in an interview that he would love to meet his father, Cecil.

‘His father got in touch

with the office and the office got in touch with me. I said to Philip, “Do you

want me to come with you when you’re going to meet your father?” “Ah, no,” he

said. I think he took Big Charlie, his roadie.’

But, according to

Philomena, father and son only met on one occasion – and not ‘five or six’

times, as Cecil’s wife Irene suggested in an interview with the MoS last year. She says Philip told her he didn’t warm to

his father. ‘Philip was never interested afterwards. I don’t think he ever

wanted to meet him again.’

Cecil Parris is, it is

understood, living out his final days in a home for the elderly. Does Philomena

have any desire to see him before he passes away?

‘No. I have not.’